A Field, A Rock, Two Farmers, And Mindfulness

When navigating life, we hit a rock and how mindfulness can transform obstacles into opportunities.

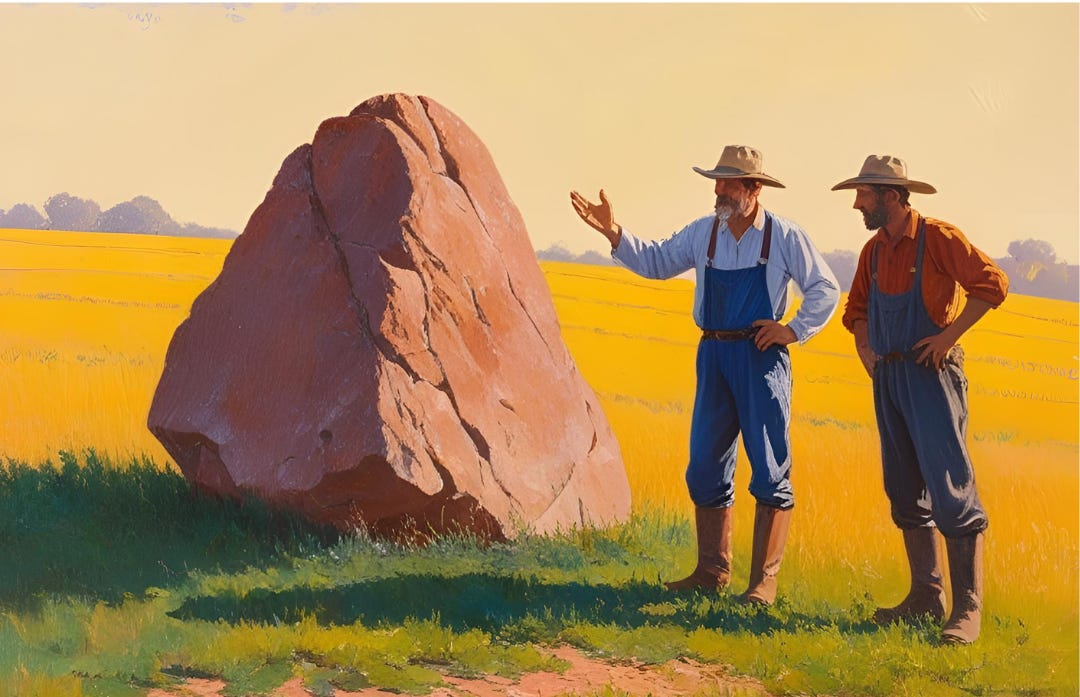

In my daily life, I often overlook the wisdom held in meeting everyday experiences with clarity of awareness, and I will be sharing something that came out of a mindfulness meditation practice related to this. It is an analogy which I like to call – “The Two Farmers” – it is an analogy that can help make sense of what is meant by the cultivation of mindfulness as an open quality of awareness.

To explore this the analogy uses the contrasting approaches of two farmers to a rock they encounter in a field to point out some fundamental principles of mindfulness, how our habitual reactions to difficulties we encounter can often increase our suffering and how mindfulness can offer a new way of approaching these that might transform the way we view difficulties in life. The story goes as follows….

The Tale of Two Farmers

Two farmers set out ploughing their fields, and while working, right in the middle of the field, suddenly their plough gets stuck. Looking at the “share” of the plough—the metal part that goes into the soil to till it—they notice that it got stuck on a rock jutting out of the soil.

The First Farmer: The Path of Resistance

On seeing this, the first farmer abruptly stops, visibly annoyed by what happened and the presence of the rock in the middle of the field. Feeling annoyed, angry, irritated and frustrated by this, he thinks to himself, “How am I going to plough the field with such a huge rock set right in the middle?”

Thinking, he says to himself, “I know, I will remove it.” So, he firmly sets his feet into the ground and positions himself to grab the rock to dislodge it from the ground. He firmly grabs the rock with his bare hands, trying frantically to pull it out of the ground, to no avail.

Feeling further annoyed, angry, irritated and frustrated, he thinks to himself, “I know, I will get a spade, dig around it, and when I reach the bottom, I will lever it out.”

He sets himself up and starts digging around it, but to no avail. All the while, the rock seemed to be just getting bigger.

Feeling tired and even more frustrated by such an outcome, he says to himself, “I know what will do the trick. I will get a mechanical digger; surely that will do it.” So, he acquires a mechanical digger and starts excavating, removing the soil and chipping away at the rock.

Finally, he says with a smile on his face and a sense of satisfaction, “The rock is gone.” He gets out of the digger and dusts off his clothes. Then, looking around, he realises that by the time he had finished, there was no longer a field to plough.

The Second Farmer: The Path of Awareness

Likewise, the second farmer, while ploughing his field, also gets his plough stuck in the middle. He stops, looks at the share of the plough, and notices that it got stuck on a rock.

Noticing this, he stops, encounters the rock, looks at it, but never loses sight of the field. He gently dislodges the plough and continues ploughing the field.

At the end of a hard day’s work, he looks at the field and again sees the rock. He approaches it, sits on it, and comes to the realisation of what a vantage point the rock is, at giving him a view of the whole field.

And such is the cultivation of mindfulness, not only in our practice of meditation but also in our actions in everyday life.

What Mindfulness Reveals About Our Reactions

This analogy reflects mindfulness as an approach, and the farmer’s contrasting responses mirrors many times what inevitably goes on in our minds when we encounter difficulties in life.

So, in our mindfulness practice and everyday life, our actions can reflect one of the two farmers, and this analogy of the two farmers can offer some insight into how we approach difficulties in our lives and our mindfulness meditation practice.

We might see that the first farmer is a representation of how we might habitually react to difficulties - with aversion, fixation, or maybe like what the first farmer did, meeting these with escalating efforts of trying to eliminate what might be a “perceived problem”.

Similarly to what happened to the first farmer when we take this approach, we might lose perspective of the whole situation and become consumed by the difficulty itself.

As we saw by focusing exclusively on removing the rock (the perceived difficulty), the farmer gradually destroyed the very field he intended to cultivate. This can mirror how we sometimes can become so caught up fighting against our thoughts, emotions, or perceived circumstances and consequences that we lose sight of the broader picture and the awareness that contains it.

The Boulder We Choose to Carry

This pattern of reactivity that we saw in the first farmer is something that contemplative traditions have pointed to (Hadot, 2016; Williams & Tribe, 2000). We can see this in a similar story shared by Shapiro and Carlson (2017), which looks at this from a different perspective. They describe a teacher who directs his students towards a large boulder and asks them,

“Students, do you see that boulder?” The students respond, “Yes, teacher, we see the boulder.” The teacher asks, “And is the boulder heavy?” The students respond, “Oh, yes, very heavy.” And the teacher replies, “Not if you don’t pick it up.” (ibid., p. 11)

Where is this taking us? What Shapiro and Carlson (2017) are pointing to here is how, at times, we might be hard at work trying to move “boulders” in our lives to where we believe they should be. Similar to the first farmer.

So, what they are alluding to here is that how we react to the “boulders” in our life can increase or reduce “suffering.” We can also see this in the way the first farmer reacted to the rock in the field and the outcome of that.

So where does mindfulness come in, and how might it help? Mindfulness offers a new way of relating to things and situations we encounter in our lives.

To make sense of this, it might help to consider how overall researchers have tried to define mindfulness as a quality of awareness. Bishop et al. (2004) point out that mindfulness has been broadly conceptualised as a,

“Nonelaborative, non-judgmental, present-centred awareness in which each thought, feeling, or sensation that arises in the attentional field is acknowledged and accepted as it is.” (ibid., p.232)

So, with mindfulness, there is the recognition that in this very moment, there is a boulder/rock and that I might not like that it is here. It involves becoming aware and familiar with our reactions to this by tuning into how it feels, noticing sensations, thoughts, and feelings that might be arising, and acknowledging that this is what there is/how I feel right now and that it is okay.

So, with mindfulness, we not necessarily trying to change our experience or be in any other way than we are right now, but it brings a non-judgmental, accepting awareness to it so that we can come to know how we might be habitually reacting to it.

So, it brings this deep, intimate knowing of what is present right now in the field of awareness.

Acknowledge how a situation might be making us feel and how easy of a tendency it might be to get caught up in frustrations, anger or annoyance - gently acknowledging how we feel without getting carried away or lost in such feelings, without losing sight of the whole situation without losing sight of the whole field of our experience just as it is.

In turn, because of this, we may begin to see how the reactivity or resistance might be the cause of our suffering, and so this, with it, brings the opportunity to choose to respond in a new way rather than react.

This might help us channel what we might call “negative emotions” more wisely so as to diligently address the situation.

Finding Space Between Stimulus and Response

As we saw with the second farmer, how mindfulness can help with something that has been attributed to have been said by Victor Frankl, the author of the book “Man’s Search For Meaning”:

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

However, ultimately, at the end of the day, mindfulness brings the clarity to see things as they are.

When Obstacles Become Vantage Points

This then brings us to the second farmer and how he embodied mindfulness in the way he approached the rock.

He acknowledged the rock - the obstacle/difficulty - but maintained awareness of the whole field - the broader situation. And within his response, we can see that rather than it being defined by resistance to what is, he works skilfully with the reality that has presented itself to him.

As a consequence of this, he eventually discovers a new reality that what initially seemed to be an obstacle/difficulty ended up not being as bad as it seemed to the extent that the rock became a vantage point from which he could see the whole field.

Some Principles for Practice and Reflection

What emerges from what I came to call the “Two Farmers Analogy” on mindfulness is a set of principles that can guide our practice. From the way the second farmer approached the situation, where in the end he ended up sitting atop what was perceived as an obstacle, we can point out the following principles related to mindfulness practice:

The importance of maintaining a broader awareness of situations rather than that narrow fixation.

The skilful approach of acknowledging difficulties without becoming consumed by them.

How resistance and aversion often end up amplifying our difficulties – “what we resist persists”.

The potential for difficulties to become teachers when approached with an open and curious awareness.

And some questions that I usually ask myself to reflect on this:

What are those rocks that I keep getting stuck on in my life?

Which are those rocks that block my awareness of the whole situation?

What are the boulders in my life that I keep trying to move to where I think they should be?

How can mindfulness help me with this? (Maybe a “breathing space” 😉)

Meeting the Rocks on Our Path

In the end, we are ultimately bound to encounter “rocks” in life - difficult emotions, physical sensations, challenging people, or circumstances. Mindfulness is not about eliminating any of these, but offers a new way of being with these by relating to them differently, with a more spacious awareness that does not lose sight of the broader context within the whole of our experience.

So, in moments like these, do not forget to stop and take a breath and tap into that space between stimulus and response, a pause that allows for choosing the way in which to respond to a situation, because in all truth, as is pointed out by the quote attributed to Viktor Frankl,

“In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

Thank you for reading this article from Now About Meditation. If you enjoyed this or think it could be helpful to someone, please do share or forward it to a friend or two, or share it on social media. 😊 It is freely available for anyone to read. 😊

If you enjoyed reading this and want to support my work, why not subscribe? 📚 Never miss a post – it's free! If you're feeling extra awesome, you can become a paid subscriber to the publication and benefit from paid subscriber content like “Subscriber-Only Posts and Posting Comments and other features”— no need for Substack, just your email address. Your support means a lot and keeps me going. 😊 Thank you! 😊

References

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., . . . Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230-241. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Frankl, V. E. (2006). Man’s search for meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Hadot, P. (2016). Philosophy as a Way Of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault. (A. Davidson, Ed., & M. Chase, Trans.) Oxford: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Shapiro, S. L., & Carlson, L. E. (2017). The art and science of mindfulness: Integrating mindfulness into psychology and helping professions (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Williams, P., & Tribe, A. (2000). Buddhist Thought: A complete introduction to the Indian tradition. London: Routledge.