The Role of Mindfulness in Breaking Dissociative Patterns: Evidence and Limitations

How might mindfulness practices break dissociative patterns? We look at evidence from studies and learn about potential limitations in applying mindfulness as a treatment for dissociative patterns.

As mentioned in our previous article on mindfulness and dissociation, practising mindfulness involves an act of will requiring a person to decide to commit into taking a particular mental course of action. This involves cultivating an intentionality of maintaining awareness of present experience with an attitude of non-judgment and acceptance, amongst others.

This is not easy, but by embarking on the path of intentionally practising this with time, mindfulness can offer a sense of psychological safety in difficult moments. Similarly, we had discussed how dissociation, as an adaptive process to block out extreme psychological and physical distress, might also offer a sense of safety when overwhelmed with emotions. However, if dissociation becomes a habitual mode of reacting to distress, it turns maladaptive, negatively effecting different aspects of a person’s life.

We also had mentioned that one crucial distinction between dissociation and mindfulness is that dissociation is a rather automatic process, while mindfulness involves intentionality. A further difference is that the negative outcomes from dissociation stem from a difficulty in holding in awareness present experience. On the contrary, mindfulness is a practice whose purpose is to cultivate awareness of present experience, and because of this, it has been suggested that mindfulness might offer a novel approach towards treating dissociation (Zerubaved & Messman-Moore, 2015).

This is not the first time that mindfulness has been suggested as a potential novel intervention for treating physical and psychological difficulties. In fact, when delivered appropriately by a trained practitioner, mindfulness has been found to help with various difficulties like anxiety, smoking, pain, and depression, some of which might incorporate within them a dissociative pattern as a coping mechanism like anxiety and depressive disorders (Goldberg et al., 2022; Goldberg et al., 2018).

It has also been suggested that mindfulness might be an effective second-line treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) due to its ability to target multiple domains related to attentional, emotional, and behavioural dysregulation (Cloitre et al., 2011). There is initial evidence for this and the potential beneficial incorporation of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) interventions in the treatment of PTSD, where dissociation is one of the symptoms of PTSD (Wagner & Caceres-Melillo, 2023).

So, we will ask the following questions: Can mindfulness help with dissociation? What is the current evidence? If so, how, and what are its limitations?

Mindfulness and Dissociation: A Closer Look at Attentional Control and Emotional Regulation

Dissociation has been increasingly linked with difficulties related to a dysregulation in emotional and attentional control (Cavicchioli et al., 2021; Lynn et al., 2019; Lynn et al., 2022). Mindfulness practice targets the stabilisation of both attention and emotional regulation through the mediating role of acceptance. Popular models of mindfulness propose that these are the core principles through which mindfulness promotes change, a process that uses attentional awareness and acceptance (Bishop et al., 2004; Shapiro et al., 2006). This has also been supported by findings from dismantling trial studies, which concluded that, although both attentional awareness and acceptance can bring about beneficial change, the latter, acceptance, might play a crucial role in mindfulness (Lindsay et al., 2018; Rahl, Lindsay et al., 2017).

Considering this, we could argue that mindfulness interventions might help break dissociative patterns by strengthening attentional control and emotional regulation through emotional acceptance. Vancappel et al. (2021) also noted such a possibility, and if, in all truth, such a link exists, they argued how this, “would make it possible to set up appropriate therapeutic programs to reduce dissociative symptoms” (ibid. p. 2).

Indeed, in the first-ever study of its kind, Vancappel et al. (2021) set out to see if this link exists and if mindfulness practice might potentially break dissociative patterns through the mechanisms of attentional control and emotional acceptance in a non-clinical sample. They recruited 312 participants who answered a battery of questionnaires to measure for, “childhood trauma, dissociative experiences, emotion regulation abilities, cognitive difficulties, attention control, and mindfulness abilities” (ibid. p. 2). Afterwards, they conducted a correlation analysis to examine if there is a positive or a negative relationship between mindfulness, dissociation, emotional acceptance, and attentional control. Below is a video explaining what a correlation analysis is.

On correlation analysis of results from questionnaires, Vancappel et al. (2021) found that mindfulness negatively effected dissociation and that difficulties related to attentional control and emotional regulation positively effected dissociation. These results mirror previous studies that mentioned how dissociation might be linked to difficulties in emotional regulation and attentional control (Lynn et al., 2019; Lynn et al., 2022). Furthermore, this link was further confirmed on conducting mediation analysis.

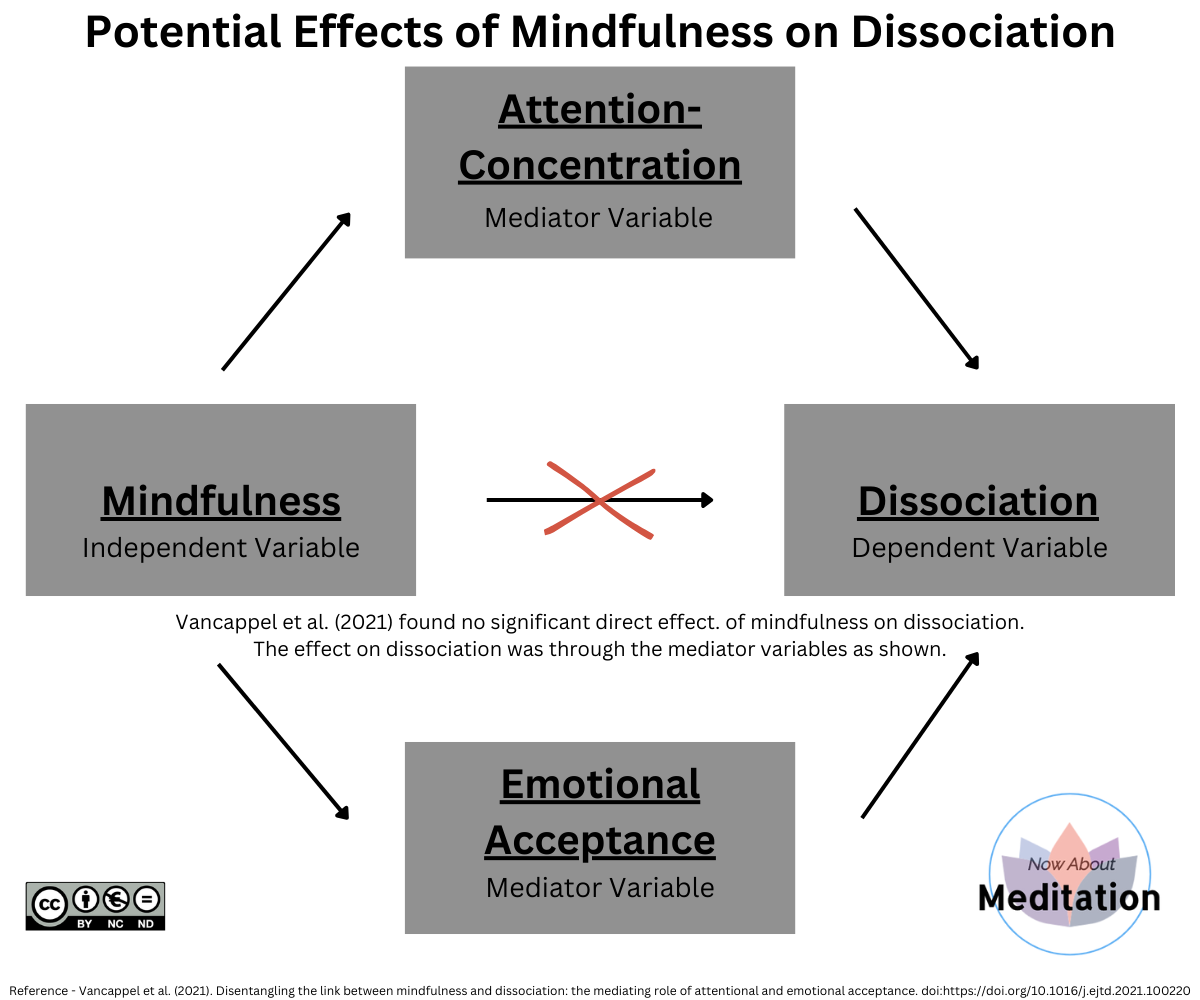

Mediation analysis helps explore the causal pathway between two variables by examining the role of an intermediate variable. In this case, the researchers are investigating the relationships between mindfulness, dissociation, emotional acceptance, and attention concentration to investigate if mindfulness influences dissociation and to understand if emotional acceptance and attention concentration are the underlying mechanisms influencing this change. Vancappel et al. (2021) found,

“That the effect of mindfulness on dissociation was mediated by attention-concentration and emotional acceptance. Our results thus indicate the mediating effects of emotional acceptance and attention-concentration on dissociation.” (p, 4)

What Vancappel and colleagues are suggesting here is that mindfulness influenced dissociation, most probably through changes in attention concentration and emotional acceptance. I made the diagram below to help represent this better.

However, they also noted a limiting factor: the study recruited a sample from the general population, limiting its generalizability, so there is no guarantee that these findings will also translate to a clinical population. Therefore, this study does not clarify if mindfulness has the potential to reduce dissociative symptoms in a clinical population through the mediating mechanism of emotional acceptance and attentional control.

Considering this, in 2023, Vancappel and colleagues reconducted the study, this time with persons suffering from PTSD, to see if their previous results would replicate with a clinical population. This time round, they recruited 90 participants suffering from PTSD who answered a number of questionnaires as per their previous study to measure for, “PTSD, history of childhood trauma, dissociative experiences, emotion regulation abilities, cognitive difficulties, attention control and mindfulness abilities” (p. 32).

Using the same procedure as their previous study, Vancappel et al. (2023) similarly found that mindfulness negatively effected dissociation. Their findings replicated earlier results where, again, this relationship seemed to be mediated by the mechanisms of emotional acceptance and attentional control.

It has to be mentioned that although both these studies are important as they shine a light on the mechanisms within mindfulness that might influence dissociation. Still, these studies did not include within them a mindfulness intervention. Therefore, despite this association, we cannot draw a direct conclusion that mindfulness practice or mindfulness-based interventions will reduce dissociative symptoms. To do this and establish a potential causal relationship, a mindfulness-based intervention needs to be carried out with individuals effected by dissociative symptoms. Vancappel and colleagues also mention this and that further research would be needed using a mindfulness-based intervention with individuals with dissociation to establish a causal relationship and if, in practice, a mindfulness-based intervention will be effective in reducing dissociative symptoms.

Can mindfulness practice directly help with dissociative symptoms?

This seems to be an issue as most studies on mindfulness and dissociation are correlational studies that use self-report measures rather than a mindfulness intervention to reach conclusions.

However, noting this deficit, D’Antoni et al. (2022) conducted one of the first preliminary studies to see if practising mindfulness meditation had a direct influence on dissociative tendencies. They stated that,

“Starting from the conceptualisation of dissociation as a continuum from normal to pathological, the purpose of the present study is to widen the knowledge of the effects of Mindfulness Meditation (MM) practice on healthy individuals’ dissociative tendencies.” (ibid. p. 9)

To do this, D’Antoni and colleagues recruited 219 “healthy” participants, who were split into two groups. 113 participants were to attend a 7-week mindfulness training, while 106 participants were assigned to a waitlist control group. In a waitlist control group, participants are initially assigned to a waiting list rather than being given immediate access to the intervention. In the case of this study those in the waitlist control were not to meditate. This is done to have a baseline with which to compare the results of the intervention group after the study.

Compared to control, D’Antoni et al. (2022) found that the participants who did the 7-week mindfulness intervention had reduced dissociative scores on the Dissociative Experiences Scale 2, in particular in the questions related to dissociative amnesia. Participants also had higher mindfulness scores on the FFMQ especially in the part of the questionnaire related to non-judgment. While on the Multidimensional assessment of interoceptive awareness questionnaire, their participants scored higher on interoceptive awareness, especially on items related to self-regulation of attention. When looking into how these results correlated together, D’Antoni et al. (2022) point out that the indications were that,

“The more participants increased in their global mindfulness skills after the training, the more they showed increased interoceptive global scores and decreased dissociative functioning.” (ibid. p. 16)

Here, we can also note how D’Antoni et al. (2022) findings seem to map onto Vancappel et al. (2021) findings that the effect of mindfulness on dissociation might be mediated by increases in attention concentration and emotional acceptance. Indeed, we could say that D’Antoni and colleague’s results also reflected this as major changes noted from participants were related to non-judgment (emotional acceptance) on the FFMQ and self-regulation of attention (attention-concentration) on the interoceptive awareness questionnaire.

Mindfulness and Dissociation: What is the current evidence?

From what we explored above, we could say that mindfulness plays a role in influencing dissociative patterns through increases in attentional concentration and emotional acceptance in both clinical and non-clinical populations.

However, I would exercise caution to say that mindfulness can help reduce dissociation in clinical populations, as the study conducted by Vancappel et al. (2023) relied on correlations obtained from using self-report measures rather than directly using a mindfulness intervention. Further, it seems that the only study that directly tested this association using a mindfulness intervention was done by D’Antoni et al. (2022), which again was done with healthy individuals who were purposefully screened for any ongoing mental or physical illness as exclusion criteria from the study.

Therefore, what we could say is that mindfulness shows potential at reducing what is called normative dissociation in “healthy individuals” or the general population but not with individuals effected by a dissociative disorder or pathology.

Normative dissociation has been used to refer to everyday experiences of disconnection from our usual state of awareness. Butler (2006) points out how, “a large proportion of the stream of consciousness is taken up with normative dissociative experiences” (p. 45). These differ from pathological dissociation (see below image), which is a symptom of a mental health disorder, and normative dissociation is a common human experience that happens to everyone, like being absorbed in a daily activity, daydreaming, fantasising, spacing out while driving all characterised by losing sense of time and space (Butler, 2006). These make me draw parallels between mindfulness and mind wandering. It makes me think about how what is being termed as normative dissociation are really related to domains of mind wandering in mindfulness.

Again, this is not to say, as we mentioned, that mindfulness might not be helpful for psychological pathologies like PTSD, anxiety, etc., that might have a dissociative element to them as one of the possible symptoms. Because as we mentioned before, for PTSD, a review found that MBSR and MBCT might be helpful with PTSD where dissociation is a potential symptom (Wagner & Caceres-Melillo, 2023).

This not being the sole study arguing for mindfulness helping with dissociation both if it is as a primary or secondary symptom (some examples, Baer et al., 2004; Escudero-Perez et al., 2016; Kratzer et al., 2018; Walach et al., 2006). Although, again, as mentioned before, most studies, including the ones referred to as examples, used solely self-report measures to test this association, so, at the same time, we cannot conclude from these studies that for sure mindfulness interventions reduce dissociation as they do not directly test this hypothesis by using a mindfulness intervention.

While more research is needed, we cannot dismiss the possibility that mindfulness might help with dissociation. Drawing from my experience teaching mindfulness and conducting mindfulness sessions, I have seen it help with normative dissociation, and instances where mindfulness helped with dissociative symptoms and patterns that were being experienced as distressing and were negatively impacting the person’s quality of life. In the latter instance, we did not use mindfulness as a first-line treatment but as a second-line treatment where residual dissociative dysregulation persisted. This means that the person had attended, for example, psychotherapy or trauma therapy, but a latent element of dissociative dysregulation remained. In such cases, mindfulness served as an effective emotional and attentional regulating strategy to address these lingering issues.

Indeed, from my practice working with individuals who were experiencing more persistent dissociative tendencies. In the right circumstances, mindfulness, with a particular focus on attentional regulation and emotional acceptance (especially compassion, self-compassion, and kindness) using elements from Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness, proved beneficial in alleviating/helping with dissociative tendencies. However, I must also point out that these sessions were highly individualised and tailored to meet the specific experiential needs of each person.

However, while mentioning this again, caution is key, and mindfulness as an approach for dissociation might not work for everyone (see previous article on mindfulness and dissociation). The person undergoing the session must be in the right frame of mind. So, to be clear, this is not a silver bullet, and research is still ongoing.

Mindfulness and Dissociation: What are its limitations?

To reiterate, although I would argue, based on my experience teaching mindfulness and current research, that:

Mindfulness can help with normative dissociation and,

Mindfulness might also potentially be helpful as a second-line treatment intervention for dissociation. This when dissociation is a secondary or one of the symptoms being experienced, and a latent amount of dysregulation remains even after attending a first-line treatment intervention, such as psychotherapy or trauma therapy, as an emotional regulation intervention.

Still, I would argue that we would be deceiving ourselves if we claimed that mindfulness is an efficacious treatment for pathological dissociative patterns or dissociative disorders like dissociative identity disorder. Notwithstanding the possibility that individuals with a dissociative pattern or pathology might dissociate during meditation or confuse mindfulness for dissociation (as discussed in the previous article on mindfulness and dissociation; see also Zerubavel & Messman-Moore, 2015)

Another limitation that might arise is that dissociation might be so ingrained as a behaviour that an individual or client might not be ready to give it up. This was something that was initially pointed out by Wagner and Linehan (1998).

Further, I do not see mindfulness practice being used as a first-line treatment for pathological dissociation, and I believe that the strength of evidence for mindfulness is as a second-line intervention for dissociation, potentially with individuals who underwent a first-line treatment but might still feel a bit dysregulated.

So to conclude, although Zerubaved and Messman-Moore (2015) concluded that,

“Mindfulness skills appear to be a feasible and potentially beneficial tool in the treatment of dissociation.” (p. 312)

And Vancappel et al. (2021) argued that,

“The link between dissociation and mindfulness may be mediated by attention and emotional acceptance. This is consistent with the model proposed by Bishop et al. (2004). Specific exercises targeting attentional control and emotional acceptance are indicated to treat dissociative symptoms.” (p. 1)

To be factual, while what they propose has some basis, and I agree with as based on my observations in practice, mindfulness might be effective for addressing dissociation, especially in cases where there is a dissociative disconnect from the body, maybe due to a “traumatic experience.” However, it is essential to note that mindfulness should not be considered a replacement for trauma therapy or first-line interventions for pathological patterns of dissociation, and as a second-line intervention, one needs to keep in mind it might not be a good fit for everyone.

We need to keep in mind that there are times when mindfulness can potentially do more harm than good for someone experiencing dissociation, particularly if the person is still emotionally fused with the experience, has repressed unresolved emotions, or is not in a place to give up a dissociative pattern.

Thank you for reading this article from Now About Meditation. If you enjoyed this or think it could be helpful to someone, please do share or forward it to a friend or two, or share it on social media. 😊 It is freely available for anyone to read. 😊

If you enjoyed reading this and want to support my work, why not subscribe? 📚 Never miss a post – it's free! If you're feeling extra awesome, you can become a paid subscriber to the publication. No need for Substack, just your email address. Your support means a lot and keeps me going. 😊 Thank you! 😊

References

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment, 11(3), 191-206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104268029

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., . . . Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230-241. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Butler, L. D. (2006). Normative dissociation. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(1), 45-62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.004

Cavicchioli, M., Scalabrini, A., Northoff, G., Mucci, C., Ogliari, A., & Maffei, C. (2021). Dissociation and emotional regulation strategies: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 143, 370-387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.011

Cloitre, M., Courtois, C. A., Charuvastra, A., Carapezza, R., Stolbach, B. C., & Green, B. L. (2011). Treatment for complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practises. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(6), 615-627. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20697

D'Antoni, F., Feruglio, S., Matiz, A., Cantone, D., & Crescentini, C. (2022). Mindfulness meditation leads to increased dispositional mindfulness and introspective awareness linked to a reduced dissociative tendency. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 23(1), 8-23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2021.1934935

Escudero-Perez, S., Leon-Palacios, M. G., Ubeda-Gomez, J., Barros-Albarran, M. D., Lopez-Jimenez, A. M., & Perona-Garecelan, S. (2016). Dissociation and mindfulness in patients with auditory verbal hallucinations. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(3), 294-306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.1085480

Goldberg, S. B., Riordan, K. M., Sun, S., & Davidson, R. J. (2022). The empirical status of mindfulness-based interventions: A systematic review of 44 meta-analyses of randomized control trials. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 108-130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620968771

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Clinical Psychology Review, 52-60.

Kratzer, L., Heinz, P., Pfitzer, F., Padberg, F., Jobst, A., & Schennach, R. (2018). Mindfulness and pathological dissociation fully mediate the association of childhood abuse and PTSD symptomatology. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 2(1), 5-10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2017.06.004

Lindsay, E. K., Chin, B., Greco, C. M., Young, S., Brown, K. W., Wright, A. G., . . . Creswell, J. D. (2018). How mindfulness training promotes positive emotions: Dismantling acceptance skills training in two randomized controlled trials. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(8), 944-973. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000134

Lynn, S. J., Maxwell, R., Merckrlbach, H., Lilienfeld, S. O., van Heugten-an der Kloet, D., & Miskovic, V. (2019). Dissociation and its disorders: Competing models, future directions, and a way forward. Clinical Psychology Review, 73, 101755. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101755

Lynn, S. J., Polizzi, C., Merckelbach, H. C.-D., Maxwell, R., van Heugten, D., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2022). Dissociation and dissociative disorders reconsidered: Beyond sociocognitive and trauma models toward a transtheoretical framework. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 18, 259-289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-102424

Rahl, H. A., Lindsay, E. K., Pacilico, L. E., Brown, K. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Brief mindfulness meditation training reduces mind wandering: The critical role of acceptance. Emotion, 17(2), 224-230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000250

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373-386. doi:10.1002/jclp.20237

Vancappel, A., Guerin, L., Reveillere, C., & El-Hage, W. (2021). Disentangling the link between mindfulness and dissociation: the mediating role of attentional and emotional acceptance. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(4), 100220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2021.100220

Vancappel, A., Hingray, C., Reveillere, C., & El-Hage, W. (2023). Disentangling the link between mindfulness and dissociation in PTSD: The mediating role of attentional and emotional acceptance. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 25(1), 30-44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2023.2231907

Wagner, A. W., & Linehan, M. M. (1998). Dissociative behaviour. In V. M. Follette, J. I. Ruzek, & F. R. Abueg (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioral therapies for trauma (pp. 191-225). The Guilford Press.

Wagner, C., & Caceres-Melillo, R. (2023). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD: A literature review. Salud Mental, 46(1), 35-42. doi:https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2023.005

Walach, H., Buchheld, N., Buttenmuller, V., Kleinknecht, N., & Schmidt, S. (2006). Measuring mindfulness—the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Personality and Individual Differences, 40(8), 1543-1555. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025

Zerubaved, N., & Messman-Moore, T. L. (2015). Staying present: Incorporating mindfulness into therapy for dissociation. Mindfulness, 6, 303-314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0261-3